Have you ever wondered about extra writing an author left out of a book you read? This post kicks-off a new series (not sure how many episodes it will be) that I’m calling, The Kitchen Sink. If you’ve read my book, Undertow, you may think I put everything in it but the kitchen sink. You’re pretty much right.

I thought it might be fun to take you behind-the-scenes to my sink museum, give you some of the left-out parts of Undertow. Let me know what you think.

As every author knows, it’s hard to cut bits and pieces and sinks that you like, that you slaved over, or that you feel are vital to the story, but cutting must be done for various reasons. Some parts don’t move the story forward, or are just too much information. Others may be interesting backstory, but not needed for that particular book.

A Catholic Girlhood

The following Kitchen Sink is backstory, a chapter titled, “Catholic Girl.” It was in a ridiculously long draft of my book from 2012. That draft was titled, Nothing But The Word. It was full of industrial-size sinks that made it 246,882 words and 728 pages. Some publishers will not even look at a manuscript of more than 100,000 words.

Note: For this online blog post, I’ve added subtitles throughout this piece.

Catholic Girl

“Whether we are aware of it or not, our culture gives us an inner script by which we live our lives.”

~ Jill Kerr Conway, When Memory Speaks

I have a photograph of little children with scrubbed 1950s faces. It depicts my second-grade class in the basement of St. Francis de Sales Catholic School. Our teachers, from the Sisters of Mercy, diligent in their long black habits and alike with “Mary” in their formal names, had arranged the scene. About sixty boys and girls, dressed meticulously in white with their hands folded in prayer, are lined up shoulder-to-shoulder on bleachers—girls on the left, boys on the right—all ready to cross a threshold: receiving their First Holy Communion.

When I studied the photograph as an adult, the first thing I did was scan each row of girls in those frilly white dresses to identify myself. A hodgepodge of expressions stared back at me, hinting at seven and eight-year-old psychological states: broad grins, uncertain smiles, inscrutable glares. Glancing from one face to the next, I was stumped. I could not be sure of the eight-year-old me. Two blonde-haired girls seemed like possibilities, but didn’t have the right haircut or shape of the nose or mouth. After a few minutes wondering where I was, to my chagrin, memories connected themselves in a rush. I realized that, of course, I would never find little Charlene in this group. I wasn’t in this picture. I wasn’t even at school that day. The photo session had transpired without me, as well as that First Holy Communion.

Salisbury, Maryland 1959

Our class would soon receive the sacrament of Holy Communion for the first time in our lives. We would meet in our church downtown where my parents had me baptized as a baby—a small granite church built on property the parish acquired in 1916. It was rock-sturdy as much from chiseled stone as from our unwavering devotion. In that Roman Catholic haven on the corner of Calvert and Bond, we found refuge and salvation.

Preparing

In preparation for Communion day, the Sisters of Mercy spent many weeks instructing us and administering appropriate quizzes and tests. They also groomed us for the non-negotiable prerequisite sacrament of Confession. During Confession, we would recite a memorized prayer called the Act of Contrition, to beg God’s forgiveness. We were also to divulge our sins to a priest. Why we couldn’t beg God’s forgiveness in the privacy of our own hearts instead of kneeling in a closet-like Confessional booth and whispering them to a priest was a question no one asked. The priest, standing in for Christ, was the only one who could ask God to wipe those transgressions off our souls, making them pure white, the only kind of souls acceptable for receiving Holy Communion. This was Church tradition and questioning it was out of the question. For kids our age, sins were usually mild anyway—no one was robbing banks, committing murder, or having affairs—nevertheless, we had to think up something bad to confess. My sins were along the lines of, ‘I annoyed my sister on purpose,’ (often true); ‘I talked too much in class’ (very often true); I refused to eat my mother’s Brussels sprouts even though she shamed me with stories of starving children in India (definitely true).

So, as directed, I slipped behind the black Confessional curtain, knelt in the booth, and through a thick screen confessed those sins. I loved it that the closet was dark and the hazy screen dividing me from the priest concealed our identities from each other. After he spoke a few times, though, I recognized his voice and wondered, embarrassed, whether he figured out which little girl I was. After the ritual was over, but before I pushed the curtain aside to leave, he assigned me an “act of repentance” —pray a few Hail Marys on the rosary—and I left with a sin-free soul. I would try hard not to stain it too quickly because a week later, in the same church, our class would take our sinless souls to Communion: a ritual involving a little white wafer called “the Holy Eucharist” or “host.” This ceremony was the centerpiece of our religious life.

Education

Our education about First Communion included the mechanics of it and its meaning. The Sisters described the physical ceremony this way: First, we were to pair up with another classmate and silently process down the middle aisle of the church all the way to the Communion railing at the front. The railing ran the width of the church, dividing the many pews for parishioners on one side, from the sacristy containing the altar for the priest on the other side. Kneeling on cushions at the railing, we were told to wait until the priest came along on the other side of the railing with his altar boy assistants, murmuring mysterious Latin words along the way, to deliver the host to us one by one. To receive it, we should tilt our heads back and stretch out our tongues so the priest could place the host on it, intoning the words, “Take and eat of this.” The Sisters warned us not to chew it, and certainly not to ever spit it out. Just let it melt until it is soft enough to swallow. Return to your pews afterwards.

The meaning of this ritual was just as clear. Even though the words, “Holy Communion,” are not in the Bible, we were taught that the gospel of Luke depicts this event, famously called the Last Supper.

Luke 22:19, 20:

v19 And he took bread, and gave thanks, and brake it, and gave unto them, saying, This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me. 20 Likewise also the cup after supper, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood, which is shed for you.”

The Sacrament

This tradition, in the Church’s view, warranted being a Sacrament, a ritual that bestows special grace on participants. Specifically, Communion would put us in immediate contact with God, making that moment the closest we could ever be to Him. Our Catholic faith, at times, promoted such a warm and intimate relationship with God that rituals were hard to resist. During Communion, this closeness was possible, they said, because of “the miracle of transubstantiation,” a fancy phrase meaning the wafer changed instantly into the body of Christ when the priest uttered the invocation. “Invocation,” another fancy word, meant, “a prayer summoning God to act.” In this ritual, God would do what the priest asked. Usually it was the other way around.

Catholics took (and still do take) these words attributed to Jesus literally, so, “This is my body … this is my blood” is exactly what it was. The priest simply asked God to turn the bread or wafer into the body of Christ allowing us to obey exactly what Jesus said to do, “Take and eat of this.” The literal Body of Christ would then become part our own physical body. The wine, also involved in this ritual, but sipped only by the priest, was likewise changed into Christ’s blood. I always wondered why we didn’t get to drink the wine, too.

Believing

These words were believable with little or no conscious effort. The mysterious morphing of the host into the human flesh of Jesus fired my imagination and fueled my yearning to connect to him, God the Son. But it also unnerved me. Communion, as holy as it was, really was awful when I thought about it. Eating human flesh? On the other hand, I was drawn to Communion because one of the kindest nuns who instructed me in the faith was my favorite, Sister Mary Claire. I trusted her. She made this eating ritual sound like a spiritual and even sensible thing to do—be in communion with God, my heavenly Father and be totally pleasing to Him. I didn’t doubt anything spoken by Sister Mary Claire. Her complexion was as white as Ivory soap and her voice just as gentle.

Indoctrinating

Sister Mary Claire taught all our lessons about Communion and some other Church dogmas, at least ones we could absorb at that age. In those days, children were taught and memorized the Baltimore Catechism. This included, among other things, doctrines and creeds like the Ten Commandments handed down from the Jews through eons of time; the seven Sacraments handed down from Church fathers through the Roman Catholic Church; and the Apostle’s Creed and Holy Scriptures, handed down from the first Christians through our church, too. Memorization and recitation seemed a sure-fire way of shoehorning us into basic theology. “Who made us? God made us,” “Who are the three persons of the Blessed Trinity?” “The Father, Son, and Holy Ghost;” “What is our purpose in this world?” “To know, love, and serve God, and be happy with him in heaven.” Thus began the Catechism, and it did not stop until we could repeat the distinctly Catholic ideas about baptism, confirmation, confession, marriage, sin, redemption, saints, relics, the Blessed Virgin Mary, papal infallibility, heaven, limbo, purgatory, and hell. Afterwards our souls were stamped with God’s blessing. We were prepared for Holy Communion. What no one could have prepared me for, however, was what kept me out of that photograph.

Disorienting

About a week before First Communion Sunday my grandmother died. Marie Lamy was my father’s mother, and she had lived up north in a nursing home. I knew she was old, she was eighty, but she was sicker than anyone had told me. Her death, in fact, shocked me. The timing of her death shocked me more.

One evening after dinner we received the sad report. Our family had recently moved to a house on Druid Hill Avenue in a neighborhood farther away from school than our previous house on Oak Hill. In the aftermath of the move, a jumble of emotional upsets related to the move began—I missed my old neighborhood friends; I missed my backyard swing; I especially missed the adventure stories about a young girl, Marie, named after my grandmother. Dad had stopped spinning the tales of Marie, declaring I was a big girl now and too old for them. With these elements of my girlhood missing, I felt lost. The night of the telephone call, I felt even more displaced.

When the phone rang, my sister and I were sitting on her bedroom floor with our cat, Dusty. The door was open to the upstairs hallway where the phone hung on the wall. I was holding Dusty whose purring soothed me. My sister was practicing her French phrases for school. At the abrupt telephone ring, Mom came out of our parent’s bedroom and into the hall to answer it. I watched Mom take off her glasses and pick up the heavy black receiver. “Yes,” she said, but spoke in such low tones I could not hear what she murmured afterwards. Then she turned away from us. Something must be wrong. After another minute, she hung up the receiver, trudged downstairs where we heard her talk with Dad. After another minute, she appeared at the top of the carpeted stairs, her freckled face streaked with tears she hurriedly wiped off. Dad, on the stairs behind her, slouched more than usual.

“I’m afraid we have sad news,” Mom began. “Grandma Lamy passed away today.”

Traumatizing

Suzie and I slumped together on the floor and Dusty sprang from my arms. Mom continued, “She was sick for so long, you know … this really is a blessing in disguise.” Dad nodded. I had seen his mother only once or twice in the nursing home, bundled up in white sheets on a motorized bed. She was incapable, by that time, of talking to anyone. I never heard her voice. She had lived, married, and given birth to five children but left her life before I had a chance to talk with her about any of it. To me, she was more of a ghost than a grandmother, even while alive.

Mom continued. “We’ll have to drive up north for her funeral … but just remember she’s gone to heaven to be with God now. She’s not suffering anymore. Let’s be thankful for that.”

Dad said nothing. They hugged us then and left us to go to bed. Before I went across the landing to my room, though, I huddled with my sister in her big antique bed for a while, listening to our parent’s muffled voices through the wall.

At the breakfast table Dad announced we must leave the next day for the funeral. It was a long drive up to New Hampshire, he reminded us, and took hours and hours. I remembered. I dreaded it. I knew motion sickness was in my immediate future and Dramamine would be the remedy. We had to prepare right away. Mom, pushing scrambled eggs around her plate, turned to me, her eyes full of worry.

“I’m so sorry about this, honey. I know your First Communion is next Sunday, but, well … we just can’t get back home in time for it.”

Grieving

I was stunned. I felt cornered with nowhere to go. That is the first time I remember feeling utterly powerless. My chance to receive Christ, my Savior in the Holy Eucharist, the one I’d been waiting for, was ripped away from me. I couldn’t get it back. Other people were in charge.

I didn’t even think to ask whether I could stay with friends to avoid missing my special day, and no one made that offer. Without protesting, I went upstairs to my room as directed. On the bed I laid out my underwear, socks, and the dress Mom said to take, folding them neatly and placing them into my little brown suitcase.

Soon Mom joined me and hung around trying to comfort me. I could receive Communion after we got back, she said, but it wouldn’t be the same and we both knew it. “Don’t worry,” she kept saying, “It’ll all work out.” But I would not be comforted. After she left the room, I kept stashing things in my suitcase despite hot tears spilling down my face.

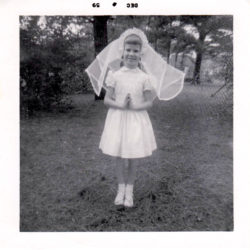

I felt as if the floor in the house had fallen through, taking me with it. I had tried so hard to get ready for this. I’d memorized all the catechism questions and answers. I’d passed my test. I’d practiced the procession with my classmates several times already. In the Church we had lined up in pairs, slowly processing down the middle aisle and splitting off to either side, filling the pews. I had my dress, a lovely handmade white one with a veil to match. We only had days to go. I loved God so much, how could He let this happen?

Trying

The next morning, Mom said she had called Sister Mary Claire and the Monsignor and asked them what to do about this terrible situation. After some consideration, they’d offered the chance for me to have a special ceremony after our trip. They also said I could invite any two girlfriends I wanted to be what they called “attendants” in the service. It would be like a wedding, incredibly special. Mom beamed as she laid out the plan, her sad eyes now picking up a sparkle. This plan sounded okay to me, but the nuns had done their job too well: I still mourned not being with my Communion class.

The funeral and associated family gatherings streamed by in a long grey blur like fog dragging down a river. When we came home, Mom got busy planning a special brunch for First Communion Sunday. Mrs. Knapp, Mom’s best friend, promised to make her delicious cinnamon coffee cake for the occasion—my favorite. I invited my friends, Lulu and Donna, not only to come for brunch but to be my attendants. At a rehearsal in the church, Monsignor explained we would proceed down the aisle like a little bride and her maids. All this festivity made Communion feel like it couldn’t come fast enough. I would finally receive the sacrament just like my classmates had. I wouldn’t feel left out anymore. I wouldn’t feel so far away from God.

Transcending

Monsignor officiated at the Mass. He reminded me of Santa Claus, only without the beard. He had white hair, a round red face, and a belly that pushed his cassock out beyond the tips of his shiny black shoes. But unlike Santa, he was a spiritual man and delivered a sermon that included mentioning me by name and explaining the special occasion. Monsignor’s actual words are lost to me, but I remember his undivided attention and that of the Sisters, my family, and many friends in the church. A hundred eyes were watching me.

As planned, I wore my new white dress, and Mom styled my hair in French braids that hung under the veil covering my shoulders. When the time came, I nervously walked down the aisle to the altar with Lulu and Donna trailing me like angels. We floated down the aisle towards the sanctuary like I imagined angels would, their wings reaching to the heavenly Father. Finally, I would be close to God like they were.

After arriving in the sacristy, where the altar stands beyond the communion railing, I knelt on the small one-person Communion bench. Entering that holy place was highly unusual, I knew, because at the time females ordinarily were not allowed beyond the limits of the railing. After a prayer, my special moment arrived. I closed my eyes, tipped back my head, and Monsignor placed the papery wafer on my tongue. It tasted like cardboard and it was just as stiff, but I knew not to chew it, just let it melt. The moment’s proclaimed impact wasn’t lost on my imagination. I did feel close to God, like everyone said I would, as if He covered me like a blanket, protecting me from evil, linking me to Him in a way no one could ever undo. I imagined that with all this glorious treatment by Monsignor, God was making it up to me for having to miss receiving Communion with my classmates. I even reasoned that since the Church’s servants represented God on earth and these servants were making a grand fuss over me, then it was just like God was doing this Himself.

Changing

For a few seconds I lingered on the kneeling bench, savoring the closeness of the invisible God and finally swallowing the host. Monsignor, although standing right in front of me, seemed strangely distant and unnecessary for my private reverie. The church with all its statues and stained glass, from the corners of my eyes, was blurry and extraneous, too. All I needed was God. I was caught away with Him like the wafts of candle smoke rising to the vaulted ceiling. It was only when Monsignor touched my shoulder and cleared his throat that I snapped out of my trance and turned around to face the parishioners. A veil had dropped between us, I felt, and a calmer version of me was standing with God behind it. During the ritual, something in my heart had shifted and settled down, like sand on the bottom of a river finding its place between stones.

The Ceremony Was Over. I was connected to God. My friends and I returned to our pew where they reached for my hands and squeezed them. They were my official Catholic sisters now. I had caught up with them in our spiritual life. I had also gained a union with God that nobody could break, that nobody’s death could ruin.

Reflecting

This circumstance imprinted my young, impressionable mind with patterns of connections tying together Almighty God, the words and actions of religious leaders, and unique events in my life like this one. Fused together in this out-of-the-ordinary situation, those elements created significance that might otherwise have passed me by if I had attended the standard Communion ceremony with my class. What none of us in my Communion situation could possibly have imagined or predicted, though, was the chance that this intertwined significance could influence, even in a remote way, future extreme behavior. Even my lively imagination held no conscious clues foretelling it. After all, who knows what choices may open to us or what limits may contain them?

Religious extremists, like the one I would eventually become, are not born that way. Fanatics, even religious ones, are made. The process may take months or years. What is predictable, however, is that thoughts, behaviors, repetitions, certainties, doubts, environments, and cultures impact people in unpredictable ways. Scanning beautiful innocent faces in a photograph can’t tell us much. Which child might end up the fanatic? Under what sets of seemingly innocuous circumstances? Raised by what kinds of parents? Instilled with what sorts of beliefs?

END

Gary

This is a superb evocation of early religious experience.

I was moved.

Excellent!

Charlene L. Edge

Oh, thanks, Gary. Glad you liked it.

Gary

I Really liked it! Great writing.

Tim

Wow, Charlene, that is beautiful. I too have the picture of innocents that you were missing from. However, your day was uniquely special as it should have been. I remember it but certainly not as well nor as eloquently as you.

You are correct that Mom’s cinnamon coffee cake was delicious, but its best aspect, from my perspective was that it was a pull apart cake and the adults had a hard time tracking who was partaking of what.

Monsignor Stout (perfect name for the man) was indeed a kind, thoughtful and wonderful man and was the cornerstone of St Francis for a very long time.

Charlene L. Edge

Hi, Tim, so nice of you to write here. I have such lovely memories of growing up with your family!

Suzanne

Dearest Sis, thanks for sharing your depth, feelings, observations and analogies. You are gifted. I’m glad you had the chance for a special day. I’m glad Dad told you stories about “Marie”. I didn’t have that experience, perhaps he was so busy going to school and working when I was little. I, too, have thought of the “host” as possibly a cannibalistic idea. I don’t remember being told to swallow it. If I go now, which is rare, I chew it slowly. I don’t drink the wine. I’ve had more mystical and spiritual revelations away from the church than in it, and believe there are many forms of divine connections. I could go on about this, but it’s been a busy day. I’m pretty sure the rosary evolved from the “prayer beads” of ancient culture. I guess, in a way, saying the rosary is a form of meditation, as the mind is totally focused in the moment. Proud of you. Thanks for sharing. Love, Suz

Charlene L. Edge

Hi Suz, appreciate your sharing here!